In this four-part technical tutorial series we will create a character-level text-generation model that can be trained to output synthetic tweets in the style of a particular Twitter user. We'll walk through the entire machine learning pipeline (see The ML Pipeline): from gathering data and training models in python, to automating the hyperparameter search process and deploying client-side models in the browser using JavaScript and Tensorflow.js. By the time we're done you should have an understanding of what it takes to develop an ML solution to a real-world problem, as well as some working code that you can use to train your own Twitter bots.

To make this project a bit more interesting, let's add some constraints. Given only a user's public Twitter handle, let's create an ML model that can generate new tweets in the style of that user, using relatively-short model training times and consumer-grade hardware like laptops or even smart phones.

These constraints will allow us to explore some creative and practical solutions to our problem that may be helpful in future ML tasks as well. Relying on "consumer-grade" hardware frees us 💸 from the leash of GPU/TPU accelerated cloud computing, and encourages us to develop a resource-limited solution to an otherwise unbounded problem. In other words, we aren't looking to find the ultimate state-of-the-art RNN text-generation solution for the tasks of automated tweet generation, but rather, we are looking for a practical "good enough" solution with limited twitter user data and compute resources. Let's get started!

Deep learning models like RNNs usually require lots of data before they begin to perform well. Anywhere from tens or hundreds of megabytes to many gigabytes of data depending on the network architecture, data representation, and task. The problem is that most Twitter users probably haven't even generated a single megabyte worth of tweets (one million characters), a dataset size that Andrej Karpathy himself claims is "very small." Even if they have, Twitter's API restricts tweet downloads to a mere 3,200 per user.

This poses a difficult problem. We have a data-hungry RNN algorithm but only very limited access to training data for a specific Twitter user. With too little data, our model will likely underfit and not be able to produce text that looks like a tweet, or even intelligible english. On the other hand, if we are able to train a model using only a few thousand tweets without underfitting, we'd likely have to train it for tens or hundreds of epochs which could lead to dramatic overfitting, or memorization of the training data; It may start to output specific lines from the training data but it wouldn't be able to generalize Twitter-like patterns, memes, or idioms like @mentions and RTs.

Wouldn't it be nice if we could somehow leverage the combined data from millions of different Twitter users instead of only the few tweets that we are afforded from a specific user that we are attempting to model? Fortunately for us, we can use a technique called transfer learning to do just that! We'll train a base model that learns to produce generic tweets in the ethos of thousands of combined tweeters. We'll then fine-tune this pre-trained base model using the sparse Twitter data we have access to for the specific Twitter user we intend to model.

In 2010, researchers at the Texas A&M University released a dataset of 9,000,000 tweets which they compiled in an effort to train a model that predicts a tweeter's location given only the contents of their tweet. We'll re-purpose this data to train our base model. In training this model, we aren't interested in a creating a model that sounds like a specific tweeter, but rather a model that learns to sound like Twitter users in general.

Let's begin by creating a twitterbot-tutorial/ directory for our project. Inside this directory we'll create another folder called char-rnn-text-generation/ to house the code and data for our base model.

mkdir -p twitterbot-tutorial/char-rnn-text-generation

cd twitterbot-tutorial/char-rnn-text-generation

The Twitter CIKM 2010 dataset is available for download from the Internet Archive. I've created a mirror of the files on GitHub which is much faster to download. I'm going to walk us through the BASH commands we'll use to download the data.

# from inside the twitterbot-tutorial/char-rnn-text-generation directory

# we'll create the folder to store the Twitter data

mkdir -p data/twitter_cikm_2010/

# download the data using wget, saving it to data/twitter_cikm_2010/twitter_cikm_2010.zip

wget -O data/twitter_cikm_2010/twitter_cikm_2010.zip https://github.com/brangerbriz/char-rnn-text-generation/releases/download/data/twitter_cikm_2010.zip

# unzip the data once it's downloaded

unzip -d data/twitter_cikm_2010/ data/twitter_cikm_2010/twitter_cikm_2010.zip

# remove the .zip once it's been decompressed

rm data/twitter_cikm_2010/twitter_cikm_2010.zip

# combine the original training and test datasets into one. We'll create our own

# training / validation / test split from this combined set.

cat data/twitter_cikm_2010/test_set_tweets.txt \

data/twitter_cikm_2010/training_set_tweets.txt \

> data/combined-tweets.txt

# create the directory where we will store training.txt, validate.txt, and test.txt

mkdir data/tweets-split/

Next, we'll extract all of the values from the tweet column in data/combined-tweets.txt and split them into three separate files: train.txt, validate.txt, and test.txt.

# here we define our train / validate / test percentage splits.

# these values MUST sum to 100. Be sure to actually enter these lines into the

# terminal to save their values as environment variables for reuse below.

TRAIN_SPLIT=80

VAL_SPLIT=10

TEST_SPLIT=10

# extracting tweets column, strip empty lines, and shuffling the data saving the

# results to data/tweets-split/tmp.txt

cut -d$'\t' -f3 data/combined-tweets.txt | sed '/^\s*$/d' | shuf > data/tweets-split/tmp.txt

# count the number of lines in tmp.txt and save the result in a variable for reuse

NUM_LINES=`wc -l data/tweets-split/tmp.txt | cut -d" " -f1`

# save the offsets for each set using the split percentages as variables for reuse

TRAIN_LINES=`python -c "print(int(${TRAIN_SPLIT} * 0.01 * ${NUM_LINES}))"`

VAL_LINES=`python -c "print(int(${VAL_SPLIT} * 0.01 * ${NUM_LINES}))"`

TEST_LINES=`python -c "print(int(${TEST_SPLIT} * 0.01 * ${NUM_LINES}))"`

# use the first 80% of tmp.txt as training data

head -n $TRAIN_LINES data/tweets-split/tmp.txt > data/tweets-split/train.txt

# use the next 10% as validation data

tail --line +"`expr $TRAIN_LINES + 1`" data/tweets-split/tmp.txt | head -n $VAL_LINES > data/tweets-split/validate.txt

# and the final 10% for testing data, data that we will use only at the very end

tail -n $TEST_LINES data/tweets-split/tmp.txt > data/tweets-split/test.txt

# clean up the temporary files

rm data/tweets-split/tmp.txt

rm data/combined-tweets.txt

That's it! You should now have 7,112,117 lines of tweet data in data/train.txt.

head -n 10 data/tweets-split/test.txt

had some phenomenal dreams about the meteor shower i missed last night

Waddup twitterers?

@MrMecc I did hit that Lebron party after all

He's my right when I'm wrong so I neva slip

DIAMOND SUPPLY CO. x RICKY ROSS

@simon_the_bunny you didn't call me.

Yey my Bros all flyin in the air hehheh

@Katieracek oh please, I have cottage cheese growing out of me! Hahaha.

@rhymeswithhappy TAKE IT (but don't move)

So are we going to carowinds?

We'll be using the popular and user-friendly Keras python library in the next section to train a model with this data, but before we do, I want to take a moment to discuss how we go from text data in a file to model training. If a machine learning model operates exclusively on numerical data, what data do we actually feed our model?

Given some sequence of input characters we'd like our model to guess a likely next character in the sequence. For instance, if our model is fed the input sequence hello ther, we'd hope that it predicts that the next character in the sequence would be e with high probability. Framed in this way, a knowledgeable observer would identify that this is a classification task, with single characters defined as both input and output classes. A naive encoding solution would use 26 classes to represent each of the 26 english characters, however, this encoding would exclude frequently used punctuation like ",", ".", and even " ". On the other hand, if we attempted to use all Unicode characters, we'd have 1,112,064 unique character classes, only a small fraction of which would actually appear in the training data. We must find some middle ground that includes enough characters to be able to accurately represent a good portion of the training data while not containing so many classes that it negatively effects our model's performance.

One common method that ML engineers use in practice is to create a class dictionary from the training data itself. If there exist 118 characters in the training data they will use that number of unique output classes. However, our training data is so large that it contains over 2,500 unique characters. Instead, we choose to pick an arbitrary set of likely characters. For convenience, we'll choose to use a subset of printable characters according to the Python programming language.

import string

print(''.join(sorted(ch for ch

in string.printable

if ch not in ("\x0b", "\x0c", "\r"))))

This produces the 97 character string below.

\t\n !"#$%&'()*+,-./0123456789:;<=>?@ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_`abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz{|}~

We'll use these characters as both our input and output classes, replacing any characters fed into the model that aren't in this list will null, effectively removing them. Next, we'll create a set of dictionaries from this list. One for quick character lookups given a character id number (where 1 points to "\t", 2 points to "\n", 3 points to " ", etc.) and the other for quick id lookups given a character.

import string

def create_dictionary():

"""

create char2id, id2char and vocab_size

from printable ascii characters.

"""

chars = sorted(ch for ch in string.printable

if ch not in ("\x0b", "\x0c", "\r"))

char2id = dict((ch, i + 1) for i, ch in enumerate(chars))

# add the null character which we'll use to represent any character not

# found in our printable vocabulary

char2id.update({"": 0})

id2char = dict((char2id[ch], ch) for ch in char2id)

vocab_size = len(char2id)

return char2id, id2char, vocab_size

CHAR2ID, ID2CHAR, VOCAB_SIZE = create_dictionary()

CHAR2ID

{

"": 0,

"\t": 1,

"\n": 2,

" ": 3,

# ...

"|": 95,

"}": 96,

"~": 97

}

ID2CHAR

{

0: "",

1: "\t",

2: "\n",

3: " ",

# ...

95: "|",

96: "}",

97: "~"

}

# 98 instead of 97 because we add the null character ""

VOCABSIZE

98

These dictionaries are useful in the process of encoding data to feed into a model, or decoding data a model outputs back into text, but we actually don't want to use use these integers to represent character classes themselves. The reason for this is that integers represent scalar values of some magnitude. In this sense, the character "~" represents a value 97 times the magnitude of "\t", which really doesn't make any sense from a categorical standpoint. Instead, we need a way to represent our categorical data such that it treats each category with the same level of importance. Or better yet, what if we could use an encoding that actually preserves or embeds information about the way the class itself is used in the training data that could be helpful to the learning algorithm. We'll discuss and use two different methods that achieve these goals.

Perhaps the most common data representation for categorical data is a method called one-hot encoding, where each category is encoded as a single vector with length equal to the number of total categories. All values in this vector are zero except the index of the class the vector represents, which is one, or "hot." Here is a toy example of one hot encoding for a DNA sequence, which has only four classes: C, G, A, and T.

CHAR2ID = {

'C': 0,

'G': 1,

'A': 2,

'T': 3

}

ONEHOT = {

'C': [1, 0, 0, 0], # index 0 is hot

'G': [0, 1, 0, 0], # index 1 is hot

'A': [0, 0, 1, 0], # index 2 is hot

'T': [0, 0, 0, 1] # index 3 is hot

}

def one_hot_encode(sequence):

return map(lambda char: ONEHOT[char], sequence)

# now, let's one hot encode this short DNA sequence

one_hot_encode('ACAATGCAGATTAC')

[[0, 0, 1, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 1],

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 0]]

One-hot encodes each class as a unit value along a unique axis, or dimension, of a multidimensional space where the number of dimensions equal the number of classes. All class label values are orthogonal with a magnitude of one, which means that our model will be able to differentiate between them in a way that is less bias than using integer valued labels.

When we train a model using supervised learning, we do so using training data that consists of X and y pairs, where each input sample from X has a corresponding expected output label y. In a classification task, it is very common to express both the training inputs X and the labels y as one-hot encoded vectors. In our case, however, we will use one-hot encoding for our labeled data and express our input data using word embeddings.

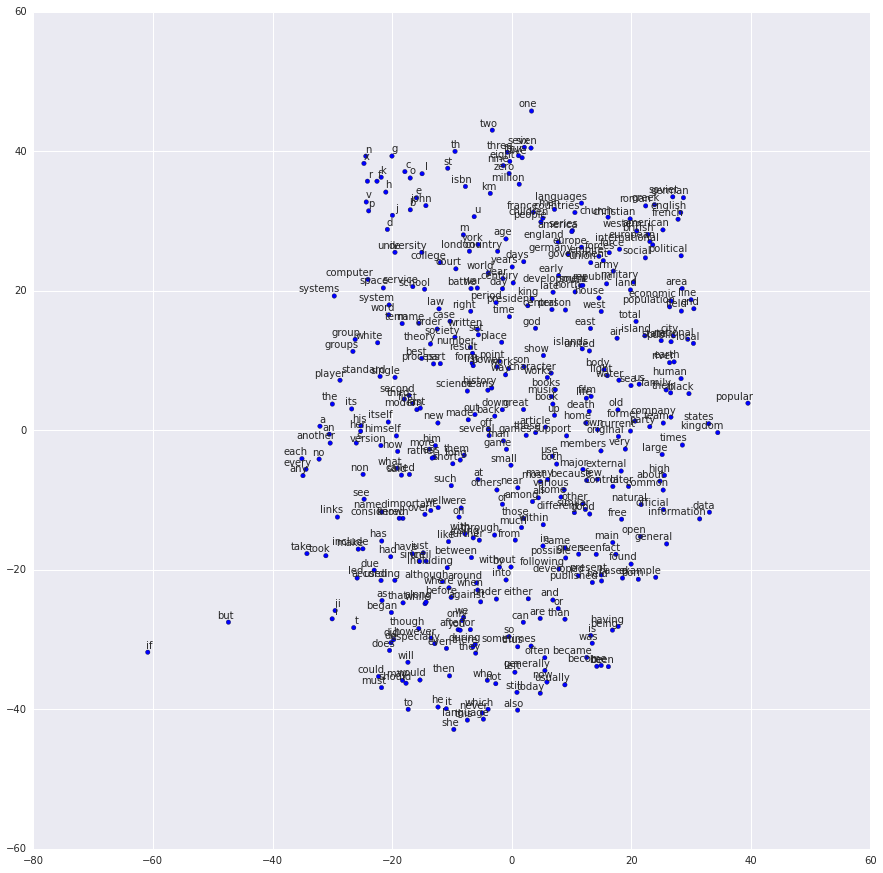

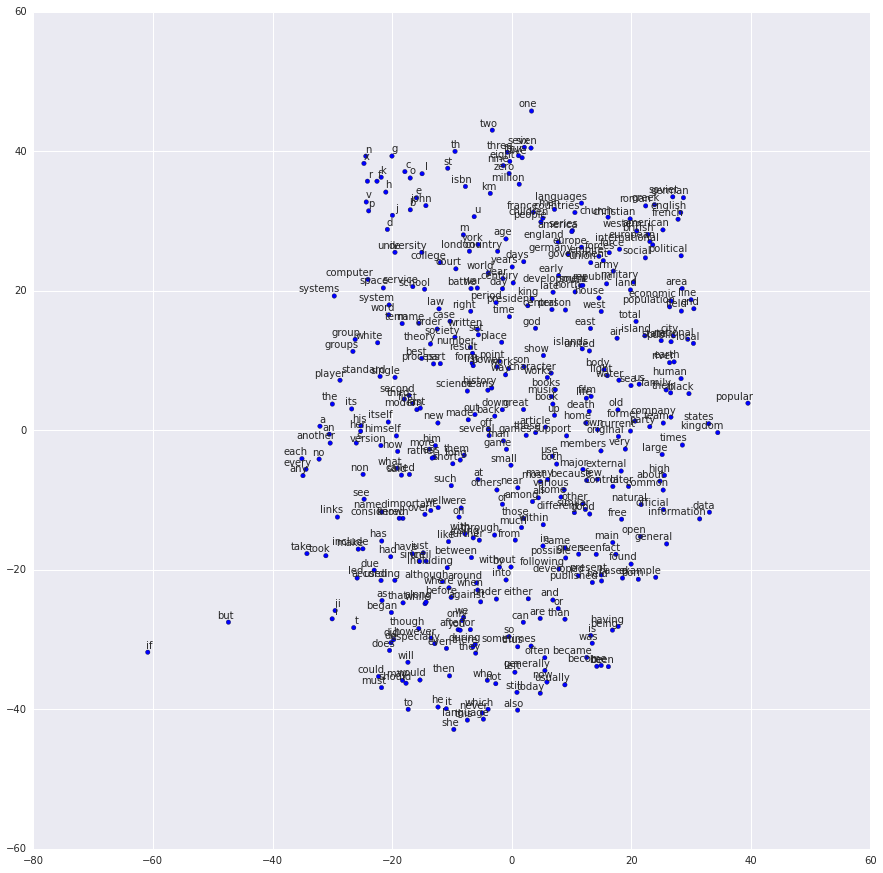

In the domain of natural language processing and generation, word embeddings are a popular encoding technique used to transform categorical data, like a word, into a continuous vector space such that information about the context and usage of that word is preserved. Once transformed, words that are similar to one another appear geometrically "nearby" in this embedding space.

One-hot vectors encode data in a way that destroys valuable information about the relationship between the labels and their usage in our training data. It is also redundant and inefficient (just look at all of those 0s). Word embeddings, on the other hand, learn an encoding that aims to preserve semantic meaning, mapping it into a geometric space. The distance and direction between any two words in this learned embedding space should represent some relationship between these two words. This idea can take a while to wrap your head around, but it's an incredibly powerful technique. This is a form of feature learning and there are several popular techniques that can be used to learn the embeddings for your particular dataset. Once learned, word embeddings are usually used in combination with a look up table, as the input data X in model training.

Here is another toy example encoding the four DNA classes, this time with word embeddings instead of one-hot encoding.

# word embeddings can be pre-trained or learned during model training

# as with the Keras embedding layer. Here we assume they are pre-trained

# and are just illustrating the look-up table process.

EMBEDDINGS = {

'C': [ 0.897, 2.922, -4.294, -0.389],

'G': [-3.103, 1.004, -2.098, 3.790],

'A': [ 0.479, -3.029, 1.189, 0.695],

'T': [ 0.127, 1.288, 5.713, 0.333]

}

def char_to_embedding(sequence):

return map(lambda char: EMBEDDINGS[char], sequence)

# now, let's one hot encode this short DNA sequence

X = char_to_embedding('ACAATGCAGATTAC')

[[ 0.479, -3.029, 1.189, 0.695],

[ 0.897, 2.922, -4.294, -0.389],

[ 0.479, -3.029, 1.189, 0.695],

[ 0.479, -3.029, 1.189, 0.695],

[ 0.127, 1.288, 5.713, 0.333],

[-3.103, 1.004, -2.098, 3.790],

[ 0.897, 2.922, -4.294, -0.389],

[ 0.479, -3.029, 1.189, 0.695],

[-3.103, 1.004, -2.098, 3.790],

[ 0.479, -3.029, 1.189, 0.695],

[ 0.127, 1.288, 5.713, 0.333],

[ 0.127, 1.288, 5.713, 0.333],

[ 0.479, -3.029, 1.189, 0.695],

[ 0.897, 2.922, -4.294, -0.389]]

# Down here we would feed X into our model with a corresponding y label that

# is one-hot encoded...

Fortunately for us, Keras provides support for both learning and using embeddings as inputs to neural network models. We'll dive into model training in the next section, but first I wanted to give you a peek at what this embedding step looks like in our python code. It really couldn't be any easier!

from keras.layers import Embedding

from keras.models import Sequential

vocab_size=98

embedding_size=32

batch_size=64

seq_len=64

model = Sequential()

model.add(Embedding(vocab_size,

embedding_size,

batch_input_shape=(batch_size, seq_len)))

# build the rest of our model down here...

Now that we know how we are going to represent our 9,000,000 plaintext tweets as numerical data, there is one more problem we need to solve: How are we going to fit all of that data in RAM without crashing our computer? train.txt's 545 MB of text might not seem like a problem if you've got 8 GB of RAM, but both one-hot encodings and word embeddings are far more memory consumptive than UTF-8 text, so once we've encoded our training data it takes up a lot more space in memory.

The solution is to manage our data using generators: lazy loading, encoding, and releasing training data as we need it. In languages that support them, generators act like pausable functions. They resume their state upon their next function call.

def my_generator():

times = 0

while True:

times += 1

# in generators, "yield" is used in place of "return"

yield "This generator function has been called {} times".format(times)

# generators are instantiated before being "called" with the next() built-in

gen = my_generator()

print(next(gen)) # This generator function has been called 1 times

print(next(gen)) # This generator function has been called 2 times

print(next(gen)) # This generator function has been called 3 times

In Keras, we can use the model training method model.fit_generator(data_generator) to train a model using data that is prepared using a generator. This method requires data_generator to produce batches of [X, y] pairs and will internally manage calls to next(data_generator) whenever it requires new training data. Below is a code snippet that illustrates how our data will be loaded, encoded, and fed into the model in the next section. I've included it here with hopes that you will take care to attempt to understand what it is doing, at least from a high-level standpoint. We'll do something with this code in the next chapter.

def data_generator(text_path, batch_size=64, seq_len=64):

# only store 1MB of text in RAM at a time

max_bytes_in_ram=1e6

# get the total size of the input file and make note of the location where

# our file last subdivides into chunks of max_bytes_in_ram. We'll never

# load data past this point. We don't want to load a 1MB chunk of text if

# there are only 420KB left in the file!

total_bytes = os.path.getsize(text_path)

effective_file_end = total_bytes - total_bytes % max_bytes_in_ram

# open the file and start an infinite loop

with open(text_path, 'r') as file:

epoch = 0

while True:

# file.tell() gives us the file reader's current position in bytes

if file.tell() == 0:

# once we are back at the beginning of the file we have

# entered a new epoch. Epoch is also initialized to zero so

# that it will be set to one here at the beginning.

epoch += 1

# load max_bytes_in_ram into RAM

# this implicitly moves the reader's position forward

io_batch = file.read(max_bytes_in_ram)

# if we are within max_bytes_in_ram of the effective_file_end

# set the file read playhead position back to the beginning,

# which will increase the epoch next loop

if file.tell() + max_bytes_in_ram > effective_file_end:

file.seek(0)

# encode this batch of text, converting characters to label integers

encoded = encode_text(io_batch)

# the number of data batches for this io batch/chunk of bytes in RAM

num_batches = (len(encoded) - 1) // (batch_size * seq_len)

if num_batches == 0:

raise ValueError("No batches created. Use smaller batch_size or seq_len or larger value for max_bytes_in_ram.")

# this part might get a little heady, especially considering that we

# haven't talked about batch_size and seq_len yet and that it relies

# on numpy (np), a utility library for matrix and vector operations.

# don't worry if this doesn't make much sense yet. The important thing

# is that we are creating and yielding batches of [X, y] training data each

# time the generator is called.

rounded_len = num_batches * batch_size * seq_len

x = np.reshape(encoded[: rounded_len], [batch_size, num_batches * seq_len])

# if we were using one-hot encoded input data, we would uncomment this

# line. Instead we will keep our x data as a list of integers that

# can be used by the Keras Embedding() layer look-up-table to create

# and learn the word embeddings.

# x = one_hot_encode(x, VOCAB_SIZE)

y = np.reshape(encoded[1: rounded_len + 1], [batch_size, num_batches * seq_len])

# we will use one-hot encoding for the labeled data, just like we

# talked about

y = one_hot_encode(y, VOCAB_SIZE)

x_batches = np.split(x, num_batches, axis=1)

y_batches = np.split(y, num_batches, axis=1)

for batch in range(num_batches):

yield x_batches[batch], y_batches[batch], epoch

That's it for data preparation! By now you should have an idea of the type of data we are using and the ways we plan on transforming it before feeding it to models in the next chapter: Part 2, Model training and Iteration.

Return to the main page.

All source code in this document is licensed under the GPL v3 or any later version. All non-source code text is licensed under a CC-BY-SA 4.0 international license. You are free to copy, remix, build upon, and distribute this work in any format for any purpose under those terms. A copy of this website is available on GitHub.